We learned to spin together freshman year, gliding across the university rink, leaning into the curves, pulling limbs in tight until the empty bleachers blurred and our ponytails flew out behind us. In class, angular momentum was dry and logical. On ice, it felt like love.

We learned to spin together freshman year, gliding across the university rink, leaning into the curves, pulling limbs in tight until the empty bleachers blurred and our ponytails flew out behind us. In class, angular momentum was dry and logical. On ice, it felt like love.

Four years passed with hours spent in the library surrounded by piles of paper filled with scratched-out equations, our fingers twined under the table. Hundreds of quick changes from jeans and t-shirts covered in equations to velvet skating dresses and warm tights. Hours on the rink learning more difficult spins, jumps, intricate footwork, cold noses brushing cheeks warmed by exertion.

The two-body problem was easy to solve in mechanics class. In real life, it proved impossible. Your career pulled you east, to study the life cycles of stars. Mine took me west, toward new theories in robotics. Visits grew rare, and silence peppered our phone calls. We were two charged particles, the force of love between us divided by the square of our distance apart.

You even stopped skating.

But all the while, my love flowed toward you like heat toward the empty side of a bed. The absence of your love was a chill that blankets couldn’t erase.

I was working late in my advisor’s lab when a college friend called from the hospital. A car of mass m traveling at speed v had gone around an icy curve of radius r. The force of friction between your tires and the road had not been enough to provide the necessary centripetal acceleration. You were dying.

Ice gripped my heart. My universe slowed, approaching its heat death.

I packed my equipment and flew to Boston, where you lay in unconscious fragility. I watched machines breathe for you until your family left us alone for a few minutes to say goodbye. That was all the time I needed for the upload. Your body died soon after.

Back at the hotel, I held the chip over the data slot and hesitated. The upload had worked, and the upload had not worked. I was afraid to collapse that wave function, but I had to. I slid the chip in place.

“Oh my god,” you said, your voice tinny over the speaker, awe showing clearly through the computer-generated voice. “You’ve done it.” A long pause, and then, “I’m dead.”

“No!” It hurt to hear you say it. “Your brain, your soul, the parts that make you you, those are alive.”

I’d only had time and space to pack the basics: camera, microphone, speaker, wheeled base, one articulated arm with a two-fingered hand. It was nothing like you, but still you.

You raised your arm, gleaming in the dim yellow light of the hotel room. You wiggled clumsy fingers in front of your face. Slowly, you said, “Thank you. But… I don’t know if I want this.”

Surprised, I asked, “You’d rather be dead?”

Silence. My heart thudded. Had the equipment malfunctioned? Had I lost you? Fingers trembling, I reached toward the diagnostic panel, but you finally spoke. “I don’t know what it’s like to die, but I never asked to become a machine.”

“You didn’t have to ask. How could I have let you die?” The thought of letting you go, of watching you fall like a ball dropped from a hundred-meter tower, wrenched my stomach. “You’re not a machine. You’re a person, a human being using adaptive technology.”

“How can I live like this?” Your voice cracked, and I adjusted the speaker.

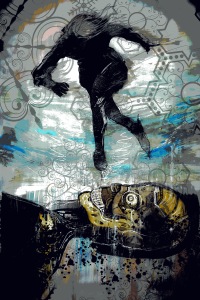

“I have better equipment back home. I’ve even designed legs with bladed feet. We could skate together again, feel the angular momentum—”

You laughed. The speaker made it sound bitter. “I haven’t skated in years. It’s not part of my life anymore.”

“With the new legs, you’d have to relearn anyway. How to balance, how to walk, how to skate. I can teach you—”

“You’re not part of my life anymore. I’ve moved on. I’m seeing someone else.”

Your words: An airplane traveling at nine hundred kilometers per hour. Me: A thirty-gram sparrow. The impact of the head-on collision took my breath away. I’d saved you, but not for me.

I thought about dismantling your silicon brain. I thought about keeping you a secret.

I thought about programming you to love me back.

You’d return to California with me. We’d skate every morning and then I’d take you to the lab with me, set you on a table to analyze your data while I worked. Every evening we’d read preprints and discuss the latest theories. We’d have the perfect life.

But as I stared into your camera-eye in the hotel room, I had to admit the truth. That life was a dream, without the rigor of even a gedankenexperiment.

We’d spun apart long ago. I’d tried to make you mine, but we were fermions, you and I: unable to be together. I called your girlfriend, and she came to get you. I returned to California to bury myself in work.

It had taken me a decade to upload a human consciousness into an android. If it took a hundred years more, I would solve the equation of our love.